Opening the boxes I shipped from my childhood home, I unpack bags of embroidery thread, needlepoint yarn, and canvases – some blank, others hosting loose drawings, and yet others that are partially filled with careful stitches. One of my nieces took sewing projects with pieces of fabric pinned in place, elaborately stitched sections, and yet more material gathered in bags, still uncut. Neither me nor my niece consider ourselves to be textile artists, and we have limited needlework experience. Yet here I am, sorting supplies, finding places for them in my own home, and wishing I had talked about the projects with the one who began them. It would be helpful to know where to start, how to use all of these supplies, and what her thoughts were about the imagery. But it is too late for that. She’s in the ground halfway across this large country, laid to rest beneath mounds of flowers.

My mom gave up a scholarship to art school and chose instead to get married and have a family. Her choice led to unexpected things: travel adventures and international living, a stable home, a comfortable life–all of which must have been amazing for a girl from the desert.

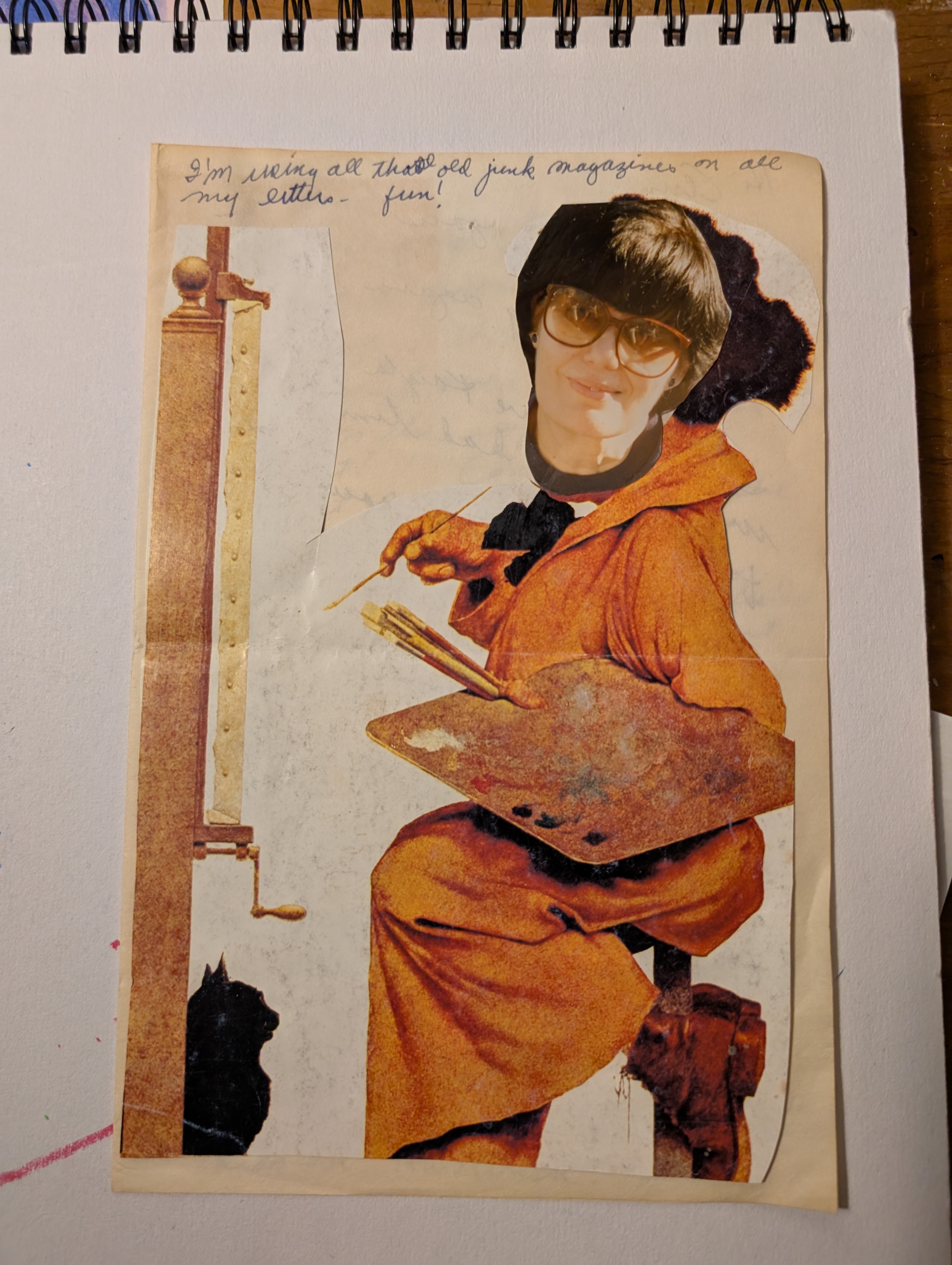

In sorting through the chaos of her things following her years of physical decline, I was able to see her artistic identity resurface. It took shape within the contents of so many boxes and notebooks: recipes clipped from magazines or written on cards (almond cake, apple galette, cheddar cheese biscuits, dark chocolate bundt cake, tequila-soaked watermelon wedges); newspaper articles about museum exhibits, pictures of sun-soaked locales, postcards from family, cards from friends, children and grandchildren; small pictures of colorful things–a Dali painting, lime popsicles, someone else’s tugboat painting, a photo of mountains in Nepal. Some pages list strange-sounding medications, with dates and check marks of what was taken and when: Eloquis, Bistolic, Metformin. Other pages have random sentences, written multiple times, almost like mantras, “Tian Taru Studio in the village of Alas Sidem on the island of Bali, the tree that grows between heaven and earth.” Some people call these scrapbooks, but I call them my mom’s sketchbooks. They are collages of her loves, her desires, and her changing reality.

When she was healthy she was prolific, working in so many media, loving beautiful things. Art permeated her life. When I was a kid she cast plaster birds in sand in the backyard and made me sit still for hours while she painted portraits. She made pieced and sewn fabric wall hangings, created embroidery and embellished needlepoints. She also sewed many quilts, including a Starry Night quilt for my 40th birthday that I sleep under during the winter (it’s got polar fleece inside so is definitely a seasonal choice). Her paintings–oil on canvas or paper–populate her family’s homes. She never really completed paintings, we just had to take them when they were available, before they were painted over into something completely different. During one of her visits, I set her up in my kitchen with a stretched canvas on the wall. Over the week she stayed with me I watched the imagery change: first a tree, then me beneath it, the next day I was facing the other way, then finally I was gone and only the tree remained. I’m in there somewhere, beneath layers of paint, forever working in the dirt beneath the blooming lilac tree that still stands in the backyard.

Seeing a recent fiber art exhibition made me think again of my mom. Her practice was a solo one, she worked by herself in her home. She had no artistic community beyond her family, and she showed her work only rarely in her lifetime. But I know she would have enjoyed this show and appreciated the efforts of women who have worked together and supported each other for so many years. She would have loved the work.

It’s a gift I received from her, this love of visual art. It’s a language we understood together. My mom knew so much about art from thinking about it, making it, and from just looking at the world. She was a smart, observant, creative force, who loved us. That’s a powerful thing to carry forward.

When I miss her, I know now that all I need to do is go look at some art work. And there she’ll be, right there with me.