Fun Home was on stage at the Forward Theater here in Madison during the fall. I was excited to see the play, and was curious to learn how this funny yet intense graphic novel about personal identity and unpacking familial mythology would translate into musical theater. How better to present a sensitive, heart-rending story about an artist figuring out who she is in relation to the loss of her father, than on a small stage, with a packed house and marvelous actors, and a musical score? It could be called genre-busting. But after seeing the play, having the chance to listen to some other old soundtrack chestnuts, and diving back into a few favorite graphic novels, I wonder if maybe musicals and comics have always been places for difficult stories. Loaded with drama and pain, yet punctuated with real joy, this play might just be the inevitable coming together of seemingly disparate artistic forms.

Musical theater is the natural home for wrenching heartbreak. I was reminded of this when, for reasons of nostalgia—or possibly in an attempt to distract me during a card game–I was recently subjected to not one, but two dramatic, emotional soundtracks: Camelot (original Broadway cast), and Les Miserables (original London cast). The distraction was perhaps effective (or it might have been just a lucky win for the kid), but the impact of this music persisted beyond the usual earworm.

Camelot. Wrenching heartbreak? Isn’t that just a silly 1960s Richard Harris and Vanessa Redgrave movie spectacle, with medieval hippies flitting about the English countryside/sound stage, playing at courtly ladies and knights? Sure, but at its heart, Camelot is a tragedy, a tale of the failure to contain evil, the devastating fall of a culture centered on love and joy. The play was based, of course, on T.H. White’s The Once and Future King, whose story humanized its medieval characters in a consideration of political ambition, emotional devotion, and utopian yearnings. Toss in some dreamy love songs, armored masculine posturing, and conniving offspring, and you have one complicated story-telling apparatus. I could go on about the similar structure underlying Les Mis–love, faith, greed, revolution–but my experience of this play is too heavily skewed. My 20-year-old-self shed a lot of tears during the production I had the privilege of experiencing in London; I still can’t consider this play separate from my original context for it.

Although musicals have always easily handled complex storytelling, Fun Home is not just another excellent example. Something else happens in this play when a graphic novel is incorporated into a stage experience. This isn’t just a play with actors telling a story. This is a play that shows an artist creating a work. When the adult Alison is on stage, watching the the scenes from her childhood and drawing what she sees, the play seamlessly melds two mediums: drawing and acting. While the story unfolds the audience sees the artist remembering and recording and creating. The stage presentation captures something that is so central in the structure of the novel: the act of drawing that not only frames the difficult narrative, but is it’s very telling. It is in the remembering and drawing where Alison finds her story. On stage, the art-making and the theater experiences are so cohesive, so neatly intertwined. What is accomplished in their close integration is a view into the experience of memory and creation. The activities involved in discovery, sense-making, and understanding are the very story that is presented in this play.

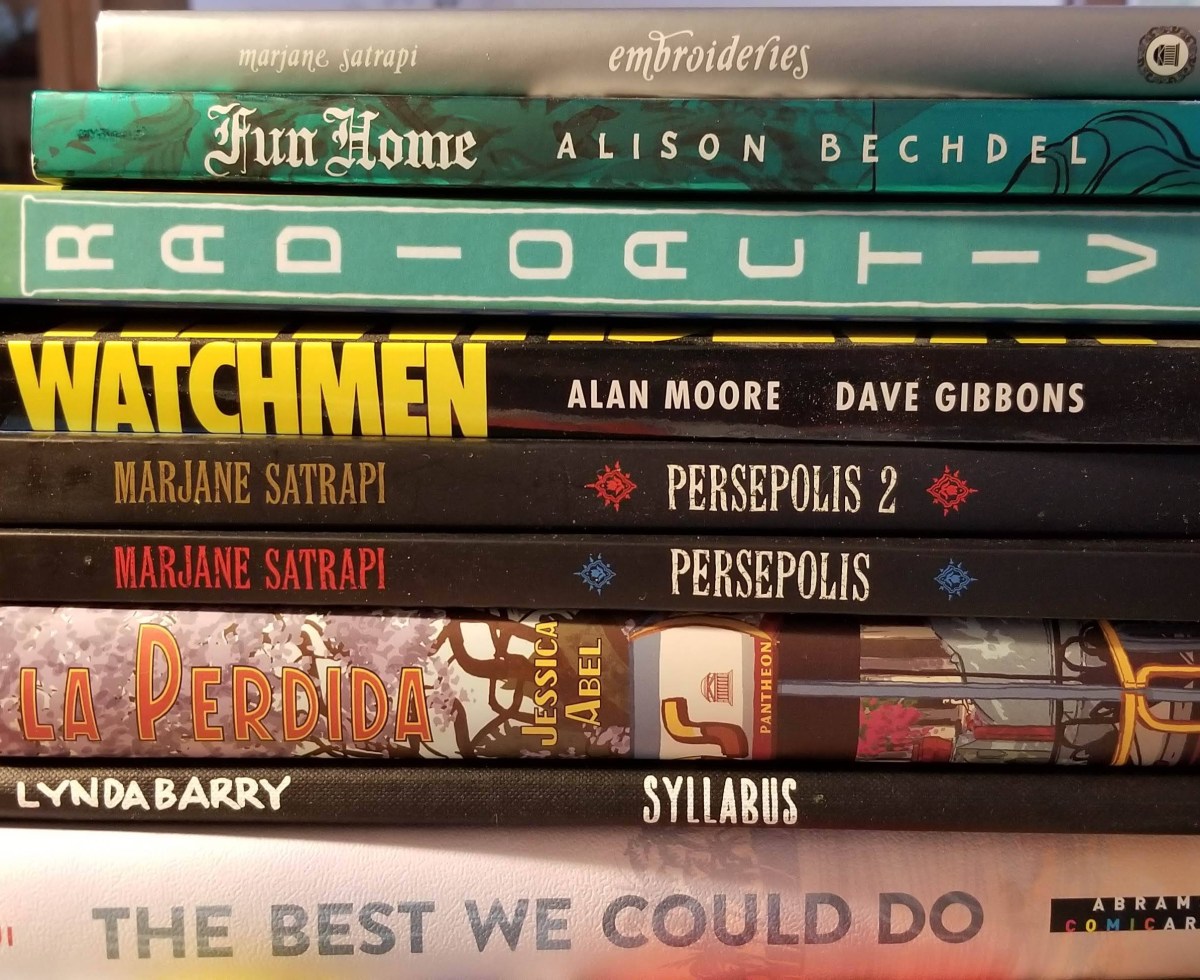

Other graphic novels have certainly handled complex and challenging stories. With visual elements emphasizing concepts that would be lost in pure text formats, the graphic novel is a powerful medium for difficult narratives. The images of water in Thi Bui’s The Best We Could Do, the laughter and faces of the women in Marjane Satrapi’s books; the cityscapes in Brian Selznick’s Wonderstruck or Jessica Abel’s La Perdida–these novels present personal narratives, visual and textual, some autobiographical, all beautifully drawn, hilarious, scary, fun, and heart-breaking.

But the form can also powerfully transform the presentation of technical material. In Radioactive, Lauren Redniss not only combines biography, history, and science education, she accomplishes this using a format that pays homage to the work of her subject, Marie Curie. By turning to drawings on cyanotypes, the work references the photographic exposure that was critical to the discovery of radiation. Its physical form is an important element in how the book is able to convey its story.

At UW-Madison, the cartoonist Lynda Barry is using drawing to explore the creative process with not only artists, but scientists. Her students have created the Applied Comics Kitchen, but there are also other efforts in visual science communication around Madison, such as JKX Comics. It’s amazing, fascinating stuff. This is not just about images, these are explorations into different kinds of stories and story-telling.

It is exciting to see compound productions like this–graphic novels and theater, storytelling that is both visual and physical. The combination of text and image, music and communication, it’s an interdisciplinarity that is so powerful. I’m not talented enough to ever be as moving and charismatic as Karen Olivio and the two younger actresses I saw in the role of Alison, but few people ever really get to that level. I do, though, think about story-telling, about how to explore and better represent complex narratives. I’m not sure my answers will necessarily involve singing (actually, I am quite certain they will not), but there are so many other forms available. A wide-ranging consideration is an important place to start.